MMT and the Language of Control: A Syntropic Diagnosis

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) has entered the mainstream as a powerful, if controversial, framework for understanding government finance. Proponents champion it for providing an accurate description of how sovereign fiat currency systems actually work. But a description is never just a description; it comes with a frame, a story, and a choice of words.

Applying The Syntropy Lens, we can diagnose the language of MMT as a form of dystropic mimesis: it masterfully mimics the language of cooperation and organic community to describe a system of pure hierarchical control. This article will explore that claim, focusing not on MMT's policy prescriptions, but on the foundational parable used to frame its description of the state.

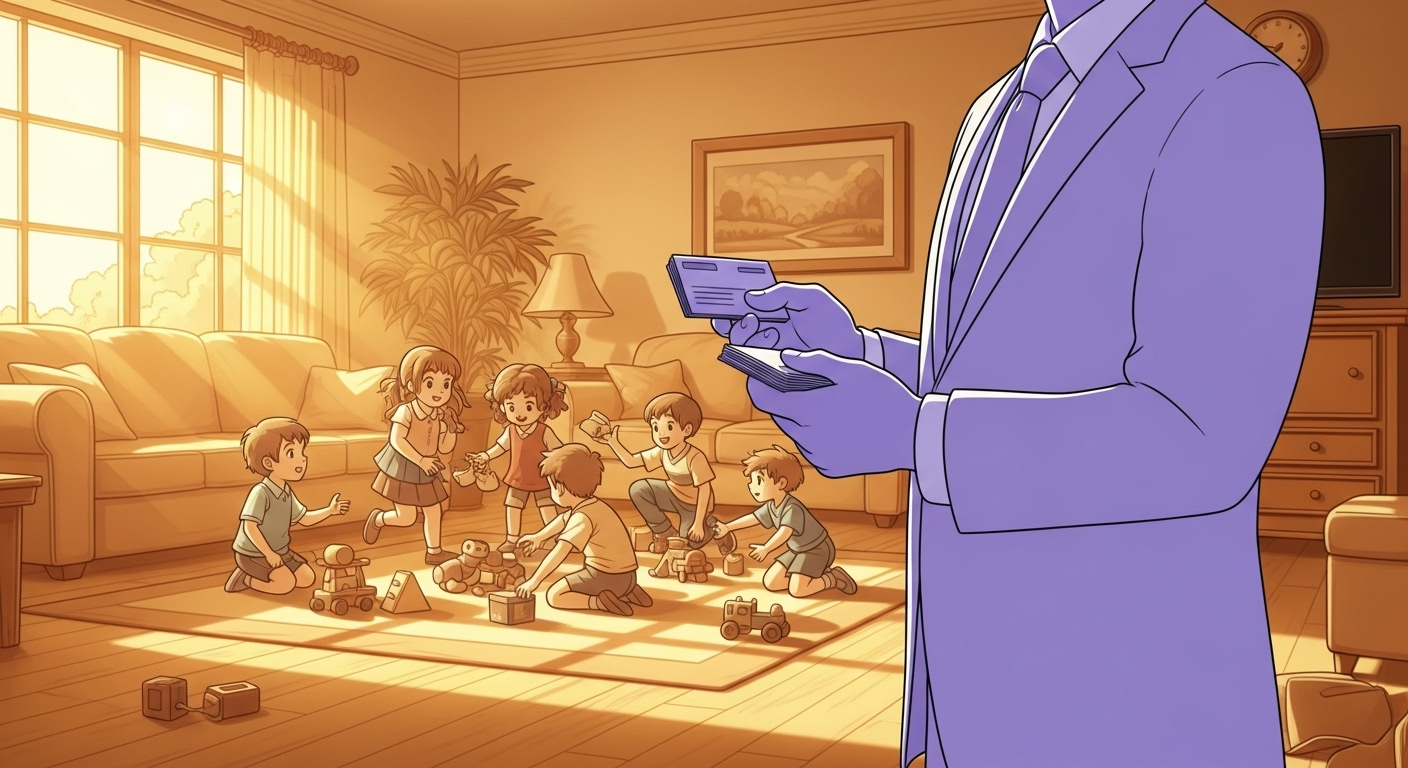

The Father, The Children, and The Business Cards

At the origin of MMT is a simple story told by its founder, Warren Mosler, to explain how a state gives value to a currency it creates from thin air. It goes something like this:

A father wants his children to do chores around the house—mow the lawn, clean the garage, wash the dishes. The children, however, have no interest. They'd rather play. The father’s offers of praise and gratitude are not enough to motivate them.

So, he devises a plan. He prints up a stack of his personal business cards. Then, he makes a new house rule: at the end of each month, each child must pay him a tax of ten business cards. Failure to pay will result in some punishment (e.g., loss of privileges).

Suddenly, the worthless business cards have value. The children now have a need for them. The father then announces that he is willing to pay one business card for each completed chore. The children, needing to earn cards to pay their monthly tax, begin doing the chores.

In this analogy:

- The Father = The Sovereign State

- The Business Cards = The State's Fiat Currency

- The Tax = The non-negotiable obligation that "drives demand for the currency"

- The Chores = The labor and resources the state can now "provision for itself" by spending its currency.

This, MMT correctly argues, is how a state can issue a currency with no intrinsic value and command real economic resources. The state doesn't need your money to spend; it needs you to need its money so it can spend its currency into existence to provision itself.

A Note on Description vs. Prescription

It's critical to pause here and draw a line. Many debates about MMT bog down by confusing its description of the system with its policy prescriptions (such as a federal job guarantee or funding social programs through currency creation).

This analysis is not about those policy prescriptions. We are taking MMT at its word—that the parable is a descriptively accurate model of the status quo. Our focus is on the language and framing of that description. The story MMT tells about itself.

Diagnosis: The Dystropic Heart of the Parable

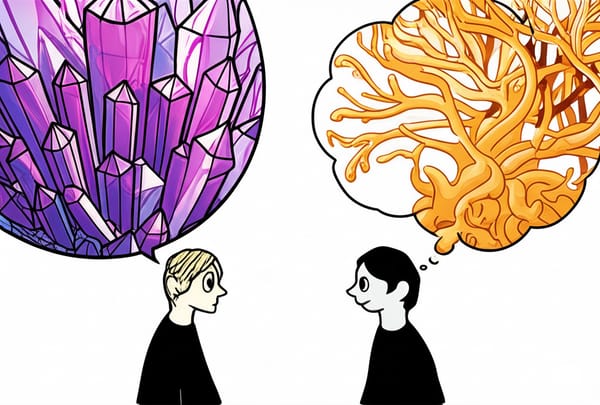

The Syntropy Lens helps us analyze the health of systems. Syntropy is the force that drives systems toward greater meaningful complexity, integration, and vitality (a higher measure of integrated information, or $\Phi$). Think of a healthy ecosystem or a high-trust community. Dystropy, its opposite, is a parasitic force that mimics syntropic processes to extract resources and impose a sterile, centralized order, ultimately reducing the system's overall health ($\Phi$).

Mosler's parable is a textbook example of dystropic mimesis in language (i.e. Doublespeak).

It uses the ultimate syntropic frame—the family home—to normalize a system of pure, non-negotiable, top-down coercion. A family is supposed to be a unit of love, trust, and voluntary cooperation. The parable hijacks this aesthetic of care to describe a power dynamic that is anything but. The father doesn't ask, negotiate, or inspire; he creates an artificial necessity and imposes a penalty.

This mimetic pattern infects the entire MMT lexicon:

- The state doesn't threaten its people with force; it "drives demand for its currency." The language mimics a neutral market force.

- The state doesn't extract resources from its populace; it "provisions itself." The language mimics an organism sustaining its own life.

- The state doesn't serve the interests of the current ruling class; it pursues the "public purpose." The language mimics a unified, collective goal.

- The entire system isn't just base colonial tribute; it's "Modern Monetary Theory." The language frames brute-force control as a sophisticated new economic paradigm.

This matters because this linguistic substitution actively damages a system's health ($\Phi$). It obscures the true lines of power and coercion, preventing citizens from having a clear understanding of their relationship with the state. This fosters a sterile order, which looks functional on the surface, over the vibrant, complex order of a society built on transparency and genuine consent.

The Path Forward: Clarity Through Apprehension

The counter-force to this linguistic fog is Apprehension—our innate faculty for sensing dissonance and seeing through a mimetic facade. To feel that the "happy home" in the story isn't a happy home at all is an act of this diagnostic clarity.

The goal (Telos) of this critique isn't to dismiss MMT's descriptive power. On the contrary, its accuracy is what makes it such a valuable object of study. By being so precise in its mechanical description while being so veiled in its moral framing, MMT unintentionally gives us a perfect tool. It teaches us to separate the what from the how—to distinguish the mechanics of a system from the stories used to justify it.

By doing so, we sharpen our Apprehension and take a step toward a society where power doesn't need to hide behind the language of care—a truly syntropic society built on clarity, not coercion.

What do you think? What should The Syntropy Lens focus on next?